Pages

▼

Friday, December 28, 2012

New screening test for diabetes unveiled

Game-changing new screening test for Type I diabetes. Read all about it on Surgery Watch. http://is.gd/pVueNk

Thursday, December 27, 2012

My seven most-read blogs of 2012

I want to again thank everyone who has taken the time to

read my blog and follow me on Twitter. I appreciate all the comments agreeing

or disagreeing with what I have written.

Interest in the blog has grown over the last year. It’s

averaging about 800 page views per day, up from 400 per day at the end of last

year. And I now have over 4200 followers on Twitter, a gain of about 2700 over

the year.

Here is a list of my top seven most-read blogs of 2012:

I hope you have a healthy and prosperous new year.

Monday, December 24, 2012

"Thousands" of errors made by surgeons

Over the last few days, stories about “thousands of errors made by surgeons” have received a lot of media and Internet attention. All of this was the result of a paper from Johns Hopkins that says surgeons leave an object in 40 patients per week, perform wrong site surgery on 20 patients per week and perform the wrong operation altogether in 20 patients per week.

The paper reported 9,744 such errors in a review of the National Practitioner Data Bank over the 20 years from 1990 to 2010. I’d love to tell you how they extrapolated from 9,744, which over 20 years averages 9.4 such errors per week, to 80 per week, but the paper is not accessible to those who do not subscribe to the journal Surgery.

I agree with those who say these are “never” events that are totally preventable and should never happen.

But I want to set the record straight.

Listen to me. Surgeons are not the cause of sponges being left in patients. I’ll explain.

A surgeon is about to perform an appendectomy. Before she arrives in the operating room, the circulating nurse and the scrub technician will have assembled all of the equipment needed to do the case. They also will have carefully counted all of the instruments, needles and sponges. [The “sponges” are not like the ones you use to clean your sink. They are 4 X 4 inch gauze pads or larger cloths called lap (short for “laparotomy”) pads.]

The surgeon has nothing to do with the counting either before or at the end of the surgery. As the wound is being closed, the nurse and tech perform another count to verify that all sponges etc. are accounted for. A third count is done after the skin is closed. There are checklists for this.

When I protested on Twitter that surgeons were being blamed for the errors involving objects left in patients, many people responded that if I was in charge, I should verify that the counts were correct. I replied that I could either do the surgery or do the counting, but not both. You see, as the case progresses, I might have asked for more equipment or a suture that was not on hand at the start of the case. The staff must add these things to the total count. If a new package of lap pads was opened, they must be counted before they can be used. Would you want your surgeon to look away from your bleeding wound to count the sponges?

Others brought up the alleged “fact” that the surgeon is the “captain of the ship.” That principle, which was established in Pennsylvania law in 1949, has been abandoned by most states. Here is a quote from a textbook on nursing malpractice:

“The viability of this doctrine is dubious, at best, in today’s health care system. Each perioperative health care provider is considered a professional with responsibility and hence accountability for specified tasks and individual actions.”

Many more such references can be found.

By the way, I wanted to see how the prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital, which is where the authors of the paper work, is dealing with medical errors. However, when I searched the Leapfrog patient safety website, this is what I found for Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Attempts to solve the problem of retained objects with technology such as barcoding sponges or placing radio frequency tags on them have not caught on. And those measures would not be able to help with instruments or needles.

Yes, no object should ever be left in a patient. But at least get the headlines straight. If nurses and techs do their jobs, surgeons cannot leave things in patients.

The paper reported 9,744 such errors in a review of the National Practitioner Data Bank over the 20 years from 1990 to 2010. I’d love to tell you how they extrapolated from 9,744, which over 20 years averages 9.4 such errors per week, to 80 per week, but the paper is not accessible to those who do not subscribe to the journal Surgery.

I agree with those who say these are “never” events that are totally preventable and should never happen.

But I want to set the record straight.

Listen to me. Surgeons are not the cause of sponges being left in patients. I’ll explain.

A surgeon is about to perform an appendectomy. Before she arrives in the operating room, the circulating nurse and the scrub technician will have assembled all of the equipment needed to do the case. They also will have carefully counted all of the instruments, needles and sponges. [The “sponges” are not like the ones you use to clean your sink. They are 4 X 4 inch gauze pads or larger cloths called lap (short for “laparotomy”) pads.]

The surgeon has nothing to do with the counting either before or at the end of the surgery. As the wound is being closed, the nurse and tech perform another count to verify that all sponges etc. are accounted for. A third count is done after the skin is closed. There are checklists for this.

When I protested on Twitter that surgeons were being blamed for the errors involving objects left in patients, many people responded that if I was in charge, I should verify that the counts were correct. I replied that I could either do the surgery or do the counting, but not both. You see, as the case progresses, I might have asked for more equipment or a suture that was not on hand at the start of the case. The staff must add these things to the total count. If a new package of lap pads was opened, they must be counted before they can be used. Would you want your surgeon to look away from your bleeding wound to count the sponges?

Others brought up the alleged “fact” that the surgeon is the “captain of the ship.” That principle, which was established in Pennsylvania law in 1949, has been abandoned by most states. Here is a quote from a textbook on nursing malpractice:

“The viability of this doctrine is dubious, at best, in today’s health care system. Each perioperative health care provider is considered a professional with responsibility and hence accountability for specified tasks and individual actions.”

Many more such references can be found.

By the way, I wanted to see how the prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital, which is where the authors of the paper work, is dealing with medical errors. However, when I searched the Leapfrog patient safety website, this is what I found for Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Attempts to solve the problem of retained objects with technology such as barcoding sponges or placing radio frequency tags on them have not caught on. And those measures would not be able to help with instruments or needles.

Yes, no object should ever be left in a patient. But at least get the headlines straight. If nurses and techs do their jobs, surgeons cannot leave things in patients.

Labels:

captain of the ship,

Medical Errors,

Reporting,

Research,

Sponges,

surgeons

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Speed bumps & appendicitis: The facts

Increased abdominal pain experienced by people when riding in a car which traverses speed bumps has been found to be a symptom of appendicitis.

As usual, several media outlets reported this topic uncritically. Medpage Today even had a video explanation of the results by an internist who suggested that this finding might one day lead to fewer CT scans being done.

I don’t think so.

Researchers from the UK prospectively questioned 101 patients with possible appendicitis, 68 of whom had ridden over speed bumps on the way to the hospital. Four were excluded because of missing data.

Increased speed bump-related pain was experienced by 54 patients, and 33 of them had appendicitis. Ten patients had no speed bump-related pain with only 1 having appendicitis.

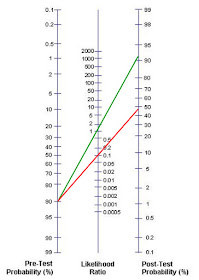

A confirmed diagnosis of appendicitis was found in 34 patients, 33 of whom had worsened pain over speed bumps, sensitivity = 97% (85% to 100%) and specificity = 30% (15% to 49%). Positive predictive value = 61% (47% to 74%); and negative predictive value = 90% (56% to 100%). The likelihood ratios (LRs) were 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) for a positive test result and 0.1 (0.0 to 0.7) for a negative result.

For a negative LR of 0.1: Suppose the patient went over a

speed bump and said he had no pain but based on other signs and symptoms, you

still think he has a 90% chance of having appendicitis. The red line shows that

a negative LR of 0.1 would give you a 48% chance that the patient actually has

appendicitis. That’s not enough to convince you not to operate.

As usual, several media outlets reported this topic uncritically. Medpage Today even had a video explanation of the results by an internist who suggested that this finding might one day lead to fewer CT scans being done.

I don’t think so.

Researchers from the UK prospectively questioned 101 patients with possible appendicitis, 68 of whom had ridden over speed bumps on the way to the hospital. Four were excluded because of missing data.

Increased speed bump-related pain was experienced by 54 patients, and 33 of them had appendicitis. Ten patients had no speed bump-related pain with only 1 having appendicitis.

A confirmed diagnosis of appendicitis was found in 34 patients, 33 of whom had worsened pain over speed bumps, sensitivity = 97% (85% to 100%) and specificity = 30% (15% to 49%). Positive predictive value = 61% (47% to 74%); and negative predictive value = 90% (56% to 100%). The likelihood ratios (LRs) were 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) for a positive test result and 0.1 (0.0 to 0.7) for a negative result.

What does a likelihood ratio mean?

For a positive LR of 1.4: The following nomogram illustrates

that if after you assess a patient with abdominal pain, you think he has a 90%

chance of having appendicitis then a positive speed bump test would increase

his odds of having appendicitis from 90% to about 92%. The green line starts at

90% and crosses the middle line at 1.4.

You can see that the speed bump test adds very little to the

diagnostic workup for appendicitis. As the MedPage video stated, it is

well-known that pain with motion is a symptom that is often found in patients

with peritonitis. I always have asked questions related to pain during the car ride

to the hospital or when riding the gurney ride to and from CT.

Further proof of the lack of utility of the test is found in

the paper itself, published in the British Medical Journal. Full text here.

In the introduction the paper states that the rate of negative

appendectomy "ranges from 5% to 42%, and this can be

associated with considerable morbidity.”

This is very old data. The standard of care in this part of

the 21st century is that the negative rate should be well below 10%.

My own rate of negative appendectomy for my last 200 cases is 4.5%.

The negative appendectomy rate for the speed bump study was

not mentioned in any of the media reports nor is it in the abstract. But the

full text of the paper reveals that the negative appendectomy rate in this

study was 20%.

I don’t see this test replacing CT scanning any time soon.

Once again to get the facts, you have to read the whole

paper, not just the abstract or the press release.

Labels:

appendectomy,

Appendicitis,

Likelihood ratio,

Reporting,

Research,

Statistics

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Electronic medical records: Documentation of care and upcoding

Electronic medical records make documentation easier and that

may be a problem.

There are many interesting unintended consequences of

electronic medical records (EMRs). I was reminded of this by a recent blog I

wrote about what interns really do when they are on call. According to a study

from a VA hospital using trained time-motion observers, interns spend 40% of

their time on a computer and only 12% of their time taking care of patients.

This meshes well with other reports noting that doctors are staring at screens

instead of talking to patients.

Here’s the problem. The system actually rewards extensive

documentation which may result in less patient contact. The saying “If you

didn’t document it, you didn’t do it” has morphed into “Document it, and you

can use a higher billing code.”

Here are some CPT billing codes for hospital visits.

99221 Initial Hospital Care, Physician spends 30 minutes at

the bedside

99222 Initial Hospital Care, Physician spends 50 minutes at

the bedside

99223 Initial Hospital Care, Physician spends 70 minutes at

the bedside

Sources tell me that they know of physicians who never bill

for less than 99223 or 70 minutes for a history and physical (H&P) examination.

In order to do this the doctor must document such things as having reviewed at

least 10 different systems (e.g., respiratory, GI, musculoskeletal etc.). This

is easy to document without having actually done it. The EMR may have popup

windows with lists of systems and symptoms that can be checked off as reviewed.

This problem is more prevalent among the so-called

“cognitive” specialties like internal medicine and primary care because for

procedure-based specialties like surgery, the H&P is usually “bundled”

(included) as part of the fee for the surgery.

Now that it is so easy to write a very detailed H&P, it

must be tempting to bill every encounter at the maximum level. However, this

may come back to bite those who try it. Medicare has been known to audit hospital

charts and office records. They have profiles of what the distribution of the

various levels of care should be.

Also, there are only so many hours in a day. Let’s say you

are working a 12-hour shift and bill for eight 75 minute H&Ps and ten 25

minute subsequent visits. That’s 600 + 250 = 850 minutes or over 14 hours. If

you are audited, you will have some explaining to do.

You may think that I am exaggerating but I am not the only

one to raise this issue.

A recent long-read from the Center

for Public Integrity confirms my thoughts. Here’s a quote from that piece,

“And Medicare regulators worry that the coding levels may be accelerating in

part because of increased use of electronic health records, which make it easy

to create detailed patient files with just a few mouse clicks.”

The article points out that billing for higher codes has

risen over the last several years and it’s costing the taxpayers over $6

billion. It warns that Medicare audits might be forthcoming, but some feel that

audits might cost more to perform than the revenue they generate.

We will see.

Thursday, December 13, 2012

How lawyers deal with being sued for legal malpractice

In 2004, a man consulted an elder-law attorney to set up a

trust that would distribute his assets fairly. He had a daughter from his

previous marriage and his wife had five children from her previous marriage.

The story is a bit complicated, but his plan was that should he die first, the

wife would inherit everything. Then when she died, his biologic daughter was to

receive all of whatever was left of the money.

But the lawyer made an error and the trust actually was

written in such a way that all six children (his daughter and his wife’s five) would

get equal shares of the estate instead of his daughter getting it all.

Sure enough, the man died first and the mistake was

discovered. The wife had not yet died but the man’s daughter sued the attorney

for legal malpractice. He admitted the error but defended himself by saying the

daughter had not yet suffered any damages so he owed her nothing. He also said

the amount of money that might be left in the trust was impossible to

calculate.

Based on the life expectancy of the wife and the amount of

money in the trust, it was estimated that the daughter should have been

entitled to over $500,000 when the wife finally dies.

The court ruled that the lawyer’s reasoning had some merit,

but because of the serious nature of the error, it awarded the daughter

$472,000 in damages.

Fine and dandy, right?

Not so fast. You see, lawyers don’t have to carry

malpractice insurance.

Here’s how the story ends: “[The lawyer] decided to declare bankruptcy, which released him from

his obligation to pay [the daughter].”

The story doesn’t mention whether the daughter had to pay

her lawyer or any other fees.

When I finished reading the article, I was infuriated. I

thought back to the origins of the medical malpractice crisis. When I was a

resident in the early 1970s, general surgeons were paying less than $500 per

year for malpractice insurance. When commercial insurers withdrew from the

market, many state medical societies hastily established physician-owned mutual

insurance companies. Shortly thereafter, premium rates shot up and here we are.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened had the medical

societies simply thrown up their collective hands and said, “What are we to do?

No one will insure our doctors.” Would state governments have stepped in? Would

that have been a good thing or a bad thing? What about the federal government?

Would we still have the ongoing crisis?

If you want to have some fun, play “What’s My Premium?” on

the New York physician-owned malpractice company’s website. You can

query any specialty in any county in the state. For example, a neurosurgeon in

Nassau County (suburban New York City) is currently paying $315,000 per year

for malpractice coverage. OB/GYN in the Bronx? $183,247.00.

In July, the New

York Times reported that some hospitals in New York are dropping their

malpractice insurance because they can’t afford it any longer, and they may not

have enough money set aside to pay judgments against them.

The hospitals use the fact that they have little money to

pay out as negotiating leverage. The hospitals tell plaintiffs to either take

what little is offered as a settlement or risk getting nothing if the hospital

goes bankrupt and closes.

Maybe the hospitals are learning from the lawyers. What

about us physicians? Will we ever learn?

Labels:

Lawsuits,

Lawyers,

malpractice insurance

Monday, December 10, 2012

In harm’s way Part II: Kidnapped MD’s rescue results in death of Navy SEAL

Almost two years ago, I blogged [here] that Americans who put themselves in harm’s way jeopardize the lives of others. I recounted the stories of mountain climbers who were rescued from a ledge, hikers who were captured in Iran and four people who went sailing in the western Indian Ocean and were captured by pirates.

Today we learn that a Navy SEAL was killed during a raid on a Taliban base which freed an American doctor who had been kidnapped last week. At least six other people died during the battle. Their backgrounds have not been detailed. [Story here.]

The doctor had been working for an organization called Morning Star Development, which runs clinics in rural Afghanistan. According to its website, Morning Star Development is a 501(c)3 charity. It addition to its clinics, it is also “training a new generation of Afghan leaders in the best practices of leadership from around the world.”

Americans can work in rural Afghanistan if they want to. I realize the people there need help.

The question is should Americans working in rural Afghanistan, who are aware of the risks they take, expect to be rescued if they are kidnapped?

You see, the problem is that someone’s son was killed saving this doctor.

I know that men who sign up for the Navy SEALs are aware that they risk death. However, it is one thing to risk death in wartime or when trying to kill the likes of Osama bin Laden.

It is something quite different to be killed rescuing a person who should not have been there in the first place.

The death of a brave Navy SEAL was unnecessary. I am angry at Morning Star Development and the doctor who caused this death. I grieve for the Navy SEAL’s family who will live with the fact that their son died while rescuing a doctor, who I’m sure had good intentions, but should not have been in rural Afghanistan.

If I were in charge, I would tell Morning Star Development and similar groups that they are free to send their people to places like Afghanistan. But if harm comes to them, they should not expect to be bailed out by my son, your son or anyone’s son.

Today we learn that a Navy SEAL was killed during a raid on a Taliban base which freed an American doctor who had been kidnapped last week. At least six other people died during the battle. Their backgrounds have not been detailed. [Story here.]

The doctor had been working for an organization called Morning Star Development, which runs clinics in rural Afghanistan. According to its website, Morning Star Development is a 501(c)3 charity. It addition to its clinics, it is also “training a new generation of Afghan leaders in the best practices of leadership from around the world.”

Americans can work in rural Afghanistan if they want to. I realize the people there need help.

The question is should Americans working in rural Afghanistan, who are aware of the risks they take, expect to be rescued if they are kidnapped?

You see, the problem is that someone’s son was killed saving this doctor.

I know that men who sign up for the Navy SEALs are aware that they risk death. However, it is one thing to risk death in wartime or when trying to kill the likes of Osama bin Laden.

It is something quite different to be killed rescuing a person who should not have been there in the first place.

The death of a brave Navy SEAL was unnecessary. I am angry at Morning Star Development and the doctor who caused this death. I grieve for the Navy SEAL’s family who will live with the fact that their son died while rescuing a doctor, who I’m sure had good intentions, but should not have been in rural Afghanistan.

If I were in charge, I would tell Morning Star Development and similar groups that they are free to send their people to places like Afghanistan. But if harm comes to them, they should not expect to be bailed out by my son, your son or anyone’s son.

Labels:

Afghanistan,

Harm's Way,

Navy SEAL,

Rescue,

Social Commentary

Friday, December 7, 2012

Is robotic surgery the “laser” of the 21st century?

An OR nurse with 40 years of experience told me that she thinks robotic surgery might go the way of the laser.

Laparoscopic surgery was introduced in the United States in 1989. Before then, gynecologists had used laparoscopes to peek into the abdomen for diagnostic purposes and tie some tubes, but removal of organs had not been done much. General surgeons didn’t use laparoscopy at all.

Some intrepid surgeons in Europe started performing laparoscopic cholecystectomies and the technique rapidly spread to the US. The rest is history.

But there is a forgotten chapter of the story. In 1990, surgeons in the US were scrambling to take courses in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It was hard to find a course that had openings. Many were sponsored by a company that made a YAG laser and the operation was originally called “laparoscopic laser cholecystectomy.”

Most surgeons abandoned the laser fairly quickly because it did not stop bleeding as well as old-fashioned cautery. Its use made the surgery take longer and result in an occasional unusual complication. The latter occurred because, unlike electrocautery which generally only burns the tissue that it touches, the laser beam kept going until it reached some tissue to burn. That something could have been the duodenum, liver or the diaphragm.

Now we have robotic surgery. So far for cholecystectomy at least, single-incision robotic cholecystectomy takes longer, is more difficult to do and may or may not be more painful than the standard 4-port laparoscopic procedure. Although touted as producing a better cosmetic result, proof that the larger umbilical incision is cosmetically better than the extra 5 mm incisions, which are usually not a concern for the average patient, is lacking. Postoperative hernia at the umbilical incision is also more common with robotic single-incision surgery.

Similar to the unusual complications seen with the laser, when robotic surgery goes bad, it really goes bad. So far, robotic cholecystectomy complications are not being reported in the literature but one hears rumors. Certainly, some unusual things have happened with robotic surgery of other organs.

There is a lawsuit based on malfunction of the robot which resulted in what the plaintiff is saying was an unnecessary conversion to open surgery.

A patient’s family successfully sued a surgeon for causing a duodenal injury during a robotic splenectomy. The patient died. It is unclear how that could have happened since the two organs are not really very closed to each other.

A woman in New Hampshire had both ureters severed during a robotic hysterectomy.

Another suit claims that the robot arms are poorly insulated which caused injuries to the intestine and an artery leading to the death of a 24-year-old woman after a hysterectomy.

The frenzy to buy robots continues but some warning signs are in the wind. I hear that a gynecology society is about to publish a position statement which will say that the use of the robot adds time and expense to procedures without impacting outcomes at all.

A big difference between the laser and the robot is cost. If I recall correctly the laser was about $100K while the robot goes for $1.5-2M plus a yearly maintenance contract of $150K plus disposables of up to $2K for every case.

Time will tell if, like the laser, the robot will end up sitting in a corner as an expensive place to hang lead aprons.

References:

Robot malfunction

Splenectomy case

Bilateral ureter injuries

Burns to intestine and artery

Labels:

general surgery,

lasers,

robotic surgery

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Study: Women with severe endometriosis are more attractive

Some researchers from Milan, Italy [it had to be from Italy] say that women with the most severe form of endometriosis are also the most attractive.

Their study involved three groups of 100 women--one group with rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE), the worst kind; a second group with peritoneal/ovarian endometriosis (POE), which is milder; and a third group who had no evidence of endometriosis.

Attractiveness was judged on a scale of 1 to 5 by raters blinded to the diagnoses of the women.

They found that 31/100 with RVE were attractive or very attractive compared to only 8/100 of the POE group and 9/100 in the No Endometriosis group. The difference was significant with p < 0.001.

Further proof of the attractiveness of the RVE women was that they first engaged in sexual intercourse at a significantly earlier age than those in the less attractive groups.

Ages of women in the three groups were similar at 32. Morphologic characteristics of the women, such as hair and eye color, BMI and waist-to-hip ratio, were similar for the three groups but RVE cohort had a significantly higher breast-to-underbreast ratio [a scientific term for big boobs].

The authors postulated that higher estrogen levels are linked with attractiveness and might also be responsible for the development of endometriosis.

The paper was published ahead of print last month in the journal Fertility and Sterility.

Some issues come to mind after reading this paper.

As they would have to be, the sexual histories of the subjects were self-reported. This sort of thing is always open to skepticism.

Four doctors, two men and two women, judged the subjects’ attractiveness. Is a panel of only four doctors sufficient to rate attractiveness? Who knows? In fairness, the inter-rater reliability of the four judges was good.

The criteria for attractiveness were not stated, so evidently “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

The rating scale of 1 to 5 was converted to a 3-point scale as follows: > 3.5 very attractive or rather attractive; 3.5-2.5 averagely attractive; < 2.5 not very attractive or not at all attractive [What must the < 2.5 group have looked like?].

I’m not a statistician but that doesn’t seem kosher to me. 1) It’s not a 5-point scale if you have decimals. 2) I believe the conversion of the scale from 5 to 3 was done to provide better numbers for comparison. Otherwise, why not have the judges just rate them on a scale of 1 to 3 from the beginning? There must not have been a statistically significant difference when they crunched the numbers using the 5-point scale.

Since the group without endometriosis serves as a control, it represents a sample of all women of Milan. Is it possible that only 9% of women in Milan, the fashion capital of Italy [some say the world], are rather attractive or very attractive?

As usual, the media reported these findings uncritically. Along with its article, a site called Medical Daily posted a sort of NSFW photograph of celebrity Padma Lakshmi, who is very attractive and has endometriosis, severity unstated. She is not a resident of Milan but did some modeling there in the past. Also, she was once married to author Salman Rushdie, who has a son named Milan from a previous marriage.

The Medical Daily headline “Why Women Diagnosed With Rare Gynecological Condition Are "Unusually Attractive" is misleading because the condition is not rare, ‘rather attractive’ is not ‘unusually attractive,’ and the study only speculates but does not explain why the women are attractive.

Cosmopolitan handled the story with typical restraint using the title “This Painful Condition Makes You Attractive,” which of course is a complete misinterpretation of the results. The short write up is accompanied by some scathing comments from endometriosis sufferers wondering why research is focused on how women look rather than curing the disease.

There is one good thing about research like this. It keeps me occupied.

Labels:

Endometriosis,

Reporting,

Research,

Statistics